TUBOS PARA DESAYUNAR, 2018

TUBOS PARA DESAYUNAR, 2018

Épargnons-nous, je vous pris, ces discours usés à la corde à propos du plus vieux métier du monde, et des maux nécessaires pour vivre en société. La prostitution est un fait accompli, certes, et ce, depuis des lustres, et je ne prétends pas en faire l’éloge ni la condamnation.

C’est surtout le contexte dans lequel la prostitution opère qui m’intéresse aux fins de mon projet d’étude. Ceci dit, je ne crois pas que ce soit une situation clémente pour l’estime personnelle de qui que ce soit d’offrir ainsi son corps au plus chérant, au premier venu.

On me dit qu’elles ont le coude léger, les filles de la rue, en Inde.

Et qu’il en va de même pour les travestis de petite vertu.

Quoique la prostitution, en soi, ne soit pas illégale au pays, bon nombre des activités qui en déclinent le sont, comme la sollicitation dans un lieu public, être propriétaire ou gestionnaire d’un bordel, ainsi que le proxénétisme. On interdit également aux conjoints de bénéficier financièrement des revenus de prostitution. L’emploi n’est légal que lorsqu’il est pratiqué dans un domicile privé, soit celui du ou de la prostituée, ou encore celui d’un tiers parti.

Et malgré que le Code pénal indien comporte le Immoral Trafficking Prevention Act, dont le but est d’enrayer le trafic humain à des fins de prostitution ; il est estimé qu’environ 90 % des arrestations portent contre les travailleuses du sexe, que l’on accuse fréquemment de troubler l’ordre public.

L'organisation américaine Human Rights Watch estime à près de 20 millions le nombre de femmes se prostituant en Inde, dont le tiers n’aurait pas encore atteint l’âge de la majorité. Selon les organisations de bienfaisance qui oeuvrent dans ce secteur, ce serait principalement le désir d'échapper à une pauvreté écrasante qui mènerait les femmes à la prostitution. Bien plus qu'une simple question de circonstance, il est essentiel d'ajouter que le corps d'une femme, tel qu'il s'inscrit dans l'espace public, est perçu comme une sorte de commodité en Inde.

Que la vertu d'une femme, et donc sa virginité, sert de monnaie d'échange pour sa famille qui perdra cette dernière lorsqu'elle intégrera l’enceinte de sa belle-famille. Dans 80 % des cas, l'agent qui reconduit une femme vers le monde de la prostitution est une connaissance, soit quelqu'un du même village travaillant déjà dans le secteur, faisant miroiter la promesse d'un emploi en ville ; parfois, ce sont, comme ici d’ailleurs, des amants se recyclant en proxénètes afin d’exploiter un corps et un coeur meurtri... Il n'en demeure pas moins que la majorité d’entre elles y entre de manière consentante, sans ainsi dire avec beaucoup d'enthousiasme...

Il ne faudrait, par contre, pas généraliser... À deux reprises, lors de mon séjour en Inde, il m’est arrivé de rencontrer des jeunes femmes qui m’ont tenu le discours suivant : « Si je rencontre un jeune homme dans un bar, et qu’après quelques verres, il me propose de l’argent pour coucher avec lui, pourquoi devrais-je refuser ? » De bonnes familles, et ambitieuses, certaines femmes voient donc la prostitution comme une aventure d’un soir, somme toute plus lucrative.

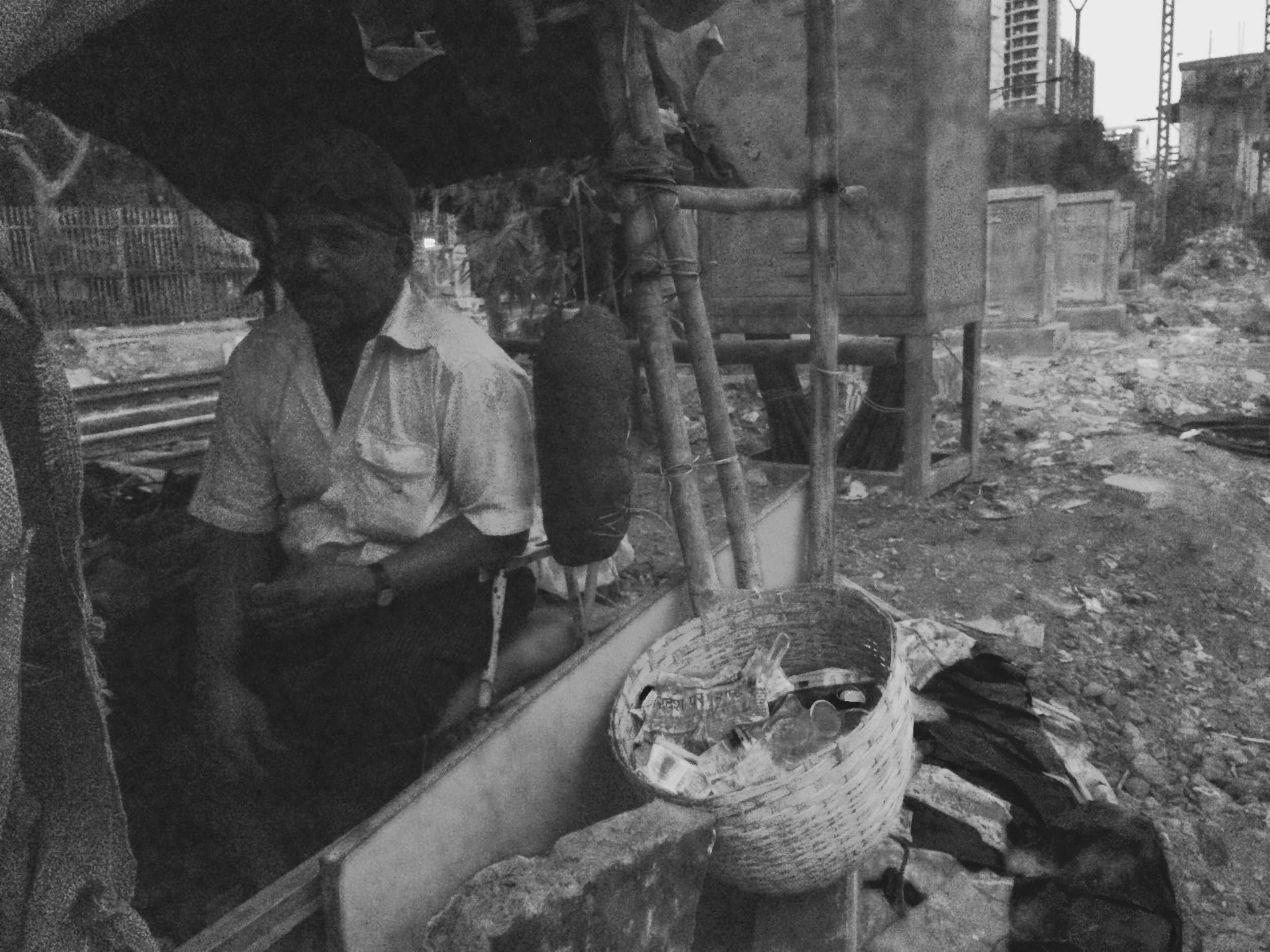

En général, la prostitution demeure une affaire de quartier, comme en témoigne le district de Kamathipura à Mumbai, où j’ai passé quelques heures à épier la faune urbaine. Les travailleuses du sexe avec lesquelles je me suis entretenue, et qui m’ont demandé des sous, puisque je monopolisais leur temps, gagnent en moyenne 500 roupies par jour, environ 10 dollars canadiens. Une escorte haut de gamme, quant à elle, va chercher entre 10 000 roupies et 500 000 roupies l’heure, soit entre 200 et 1 000 dollars canadiens. Somme dont l’agence se réserve généralement la moitié du gain puisque c'est elle qui se charge de procurer les clients.

C’est une industrie en plein essor, souvent associée à la mondialisation de la luxure et la montée du capitalisme en Asie.

En juillet dernier, alors que le gouvernement indien a tenté de censurer plusieurs centaines de sites web pornographiques, dont certains sites de rencontre, aucun des nombreux sites d’escortes ne figurait parmi la liste des 857 adresses visées par le Département des télécommunications.

Sur place, j'ai eu le droit à quelques tentatives d'intimidation de la part d'une des filles du groupe. Elle : « Tu va me ramener dans ton pays, me trouver un emploi ? » Moi : « Tu as d'autres compétences professionnelles qui te serviraient au Canada ? Tu crois que c'est en dépendant de la charité d'autrui que tu vas t'en sortir ? » Pallavi, ma gentille traductrice, n'a pas traduit. On est resté là à se dévisager jusqu'à ce que la matrone intervienne. « La fougue, avec le métier qu'on fait, c'est essentiel, » finit-elle par ajouter. Le travailleur social qui nous accompagne est explicite lorsqu’il nous interdit de nous aventurer au cœur des 14 allées qui sillonnent le quartier.

Le lendemain, de retour au bureau, ma collègue m’explique que le sort des femmes que j’ai rencontré est souvent bien plus favorable que celui de plusieurs autres... « Les filles à qui tu as parlé, » me dit-elle, « au moins elles interagissent avec leur entourage... elles peuvent prendre l’air. Dans bien des cas, la matrone doit payer une redevance aux policiers pour y rester, elles entretiennent donc des liens relationnels avec les autorités, ce qui les protège un peu... Ce sont les maisons closes qui opèrent dans le centre du quartier qui sont les pires. Là, les femmes sont traitées de manière immonde, enfermées, violées, battues, ne voyant jamais la lumière du jour. Elles sont généralement vendues par un entremetteur à une ou un proxénète, qui s’assurera de garder les affaires en ordre. On charge généralement beaucoup plus que ce que tu as entendu, mais ce n’est jamais les filles qui en bénéficient. »

Il n’y a pas que les femmes qui se prostituent, cependant. Un autre de mes collègues, qui fait son doctorat en Amérique, s’est penché sur la question de la prostitution masculine. « Il y a beaucoup d’hommes hétéros qui font ce métier, » me dit-il, « Mumbai attire beaucoup de jeunes hommes qui rêvent d'une carrière d’acteur à Bollywood. Ils viennent généralement de régions plus éloignées, et sont issus de milieux ruraux où il n'y a pas beaucoup d'accès à l'éducation. Ayant de la difficulté à se trouver un emploi, beaucoup d’entre eux se tournent vers prostitution. » Ainsi, bon nombre d’entre eux deviennent masseurs, développant un réseau de clients et d’amis à qui ils offrent leurs services. Parfois, ils font la rue, cognant sur une bouteille de vitre pour signaler qu'ils sont libres.

La question se complique lorsqu'on aborde la question de la sexualité. « Plusieurs d’entre eux ne s’identifient pas comme homosexuel. » En effet, l'homosexualité en Inde est davantage construite comme une dualité entre le rôle passif et le rôle actif, où l'homosexualité est généralement associée à un homme plus efféminé. « Pour eux, c’est un boulot, un moyen de faire de l’argent rapidement. » Il me raconte le jour ou il a demandé à un de ses répondants, qui admet entretenir des relations sexuelles avec des hommes, mais ne se considère pas comme homosexuel, comment il en était venu à cette conclusion. « Je ne me laisse jamais pénétrer, » dit-il, « c’est toujours moi qui ai le rôle actif... » Sur quoi, mon collègue, qui est, lui, très clairement et ouvertement, homosexuel, s'enquiert au sujet des considérations biomécaniques de son métier... « Quand je n’arrive pas à bander, je pense à l’argent, et ça marche... » Lui aurait-on répondu...

C’est probablement une des conversations qui m’a le plus marqué durant mon séjour. Pas nécessairement parce que je trouvais l'attitude du jeune homme déplacée, ou choquante, mais surtout à cause de la compartimentation émotive qui résulte ultimement des choix quotidiens de cette section de la population. Dans un contexte national où le dialogue public sur la sexualité est quasi inexistant, il devient difficile de faire la part des choses lorsque le tout devient une activité commerciale. Plusieurs des hommes qui se prostituaient interviewés par mon collègue disaient ne pas croire en l’amour. On y aspire, certes, en secret, mais on ne croit pas que cela soit vraiment possible. Pourtant, et contrairement aux femmes, plusieurs d’entre eux s’en sortent, trainant leur bagage émotif, leur lassitude, et l’idée que, le sexe, c’est avant tout une histoire de gratification, vers de nouvelles vies tout aussi anonymes.

En dernier lieu, j’ai aussi été marqué par le fait que la plus grande différence entre une femme qui se prostitue et un ou une transgenre, dont les clients sont surtout chauffeurs de camion ou travailleurs migrants — ce ne sont pas tant les tarifs, mais bien les sommes astronomiques qu’elles doivent débourser en frais de vêtements, de bijoux et d’accessoires, d’implants et de postiches…

On me dit que c’est cette nécessité de bien paraitre qui les rend plus avares ; et donc, plus à risques.

Dans les médias:

La photographe Japonaise Shiho Fukada photographie une communauté transgenre de Villupuram, dans l'état du Tamil Na

Le projet du photographe Charles Fox documente l'industrie du massage masculin à Mumbai.

La campagne de prévention "My husband made me a prostitute" contre l'alcool au volant :

Thursday, March 30, 2015

As our field visits draw to an end, I realize that they provide only a glimpse into the underground world I am attempting to unravel. The sheer complexity of the environments, and the subsequent advocacy efforts, leaves me wondering for days on end.

Most are clean 2 ½’s apartments; clad in various maps of the districts and hand-drawn prevention posters, spread over 600-800sqft. Some are more far more colourful or convoluted than others.

It really depends on where the doctor’s office is.

As we take our seats in the now familiar plastic patio chairs, I notice the drift from the bathrooms down the hall. I gag. The project manager from this office was voted MVP of the NGO this year. I try to breathe through my mouth as much as possible, because we should be here for a while.

The site has been operating since 2009, swept into the National Aids Control Organization’s administrative review in 2011. The staff is comprised of twenty peer-outreach workers, 6 outreach workers, a project manager, a doctor, a counsellor, and a doctor.

Sameer has been working as an outreach worker in Aarambh II for the last 6 years. The drop-in center services 6 different cruising sites, including Grant Road and Churchgate station. It is the best place to find “office boys” because the district of Colaba is the commercial hub of the city. These areas are also the ones that see most of the daily traffic.

It also happens to be one of the only areas in Mumbai where I come across other foreigners with regularity. Sometimes there is an awkward dance, where I look at them, and they look at me, and usually, we just move on. These are the office’s “star locations” because they see most of the daily traffic.

I am told that these sites are the original stomping grounds for Humsafar Trust’s initial outreach programs. Pallav, Santosh, Ashok and Vivek – who all work with me, are among the original few who were activists in the 90’s.

Sameer says most of the groundwork he does consists of relationship-building and good networking. Because avoidance is such a big part of Indian society, you have to be, at the very least clever or very handsome, to be able to approach educated people and try to inform them about things issues they don’t feel like addressing.

I’m told that some clients are reluctant to take the government-issued condoms because of the perception that nothing good can possibly be free in this country. And so, Sameer tells us, HST decided to team up with another brand, marketed by DKT India, that has better packaging.

Government-issued FREE condom

Fancy packaging condom.

When I get home, I check the expiration date on the goods. (Of course, they gave us free condoms.) April 2015. I think of the five or six big boxes I’ve spotted sitting under the desk. Are condoms like food? Still good for a couple of days after the expy date?

There are 1,500 MSMs registered at Aarambh II. They are generally given 3-4 condoms a week.

Pallavi asks about STD prevention, and about how NACO labels sexual activities. The problem is that India’s National Agency on AIDS management has decided that anal sex is the only sexual activity relevant in their guidelines.

Sex is such a taboo in India. There is no sex-ed in school. Women find out about their menstrual cycle from their mothers, aunts and friends, and the information is often a mix of facts and absurdity. So this incomplete discourse, with some much left to an active imagination, does a great deal of disservice to the cause.

The counsellors get around this lapse of judgement through a generous redistribution; a few extra here and there, just to be safe.

In response to Pallavi’s questions about STD-prevention, we are shown a flipchart booklet. It is dubiously illustrated and comprised of several pages with short topical paragraphs (I am told). From my understanding, the booklet also includes information about potential symptomatic effects on pregnant women.

Most new clients are invited to register with the counselling office after an initial assessment period of 1-2 months. His clients include a lot of migrant workers, and not everyone sticks around.

Sameer stresses that how you approach clients should vary according to who your target is. He says that high-class clients usually respond relatively well, but that they aren’t necessarily interested in hearing about sex education. So an indirect approach, like using social networks or friends to bring them around to the subject, has yielded better results. For the lower-class clients, the main concern is generally maintaining anonymity. They don’t necessarily have the social savvy to stand up to cops or the tools to mitigate any backlash that might accompany gender/sexual identity issues in India.

Of all the counsellors I’ve spoken with, Sameer is definitely the most in-tune with the bigger picture.

When we ask him how he feels about the drawbacks from NACO’s guidelines, like the age group dead zones (under 18 and over 50 age). He tells us Pallav, at HQ, is working on targeted interventions for these groups.

Despite the fact that the 50+ demographic is perhaps the least sexually active, they are the biggest clients for commercial sex. Because sex has become a commercial transaction, protection is rarely part of the equation. Studies have shown that the older demographic (in most societies) if far less likely to consult a physician, or seek out help or support. The reasons vary, of course, from not wanting to be a bother people to concerns over being recognized, but the consequences are often the same: isolation, depression, and a protracted stigma.

For Sameer, the point of leverage for change is educating youth. He recounts how complicated it is just to get admitted into the school. On one occasion, it took him over 3 months to set up an appointment. He has to use subterfuges and mind games just to get a foot into the door: he often doesn’t mention what organization he works for, at first, and usually prefers the premise of doing youth engagement.

He also cites media disinformation as a recurring problem. He mentions a newspaper article, printed last week in the Times of India, which ascribes to homosexuals a lion share of the blame for the propagation of HIV in India. We discuss the viability of a web-based video campaign to promote safe sex, and demystify a number of key subjects, from masturbation to menstruation, that are currently being completely distorted via official channels.

Mental health issues are the second biggest problem. He says at least 50% of the HIV+ patients he sees are bitter about being infected and consciously pass it on to various partners, as a means of social reprisal. It is a vindication for their despair because it becomes shared, generalized. It is a way to control a situation where perhaps you feel you have none, because this disease has taken over your life.

Substance abuse is also prevalent among youths. I am told that some TG’s and Khotis think using drugs will make them thinner, and more attractive. They haven’t seen the “Don’t Do Drugs” campaigns of the 80’s; the hollowed faces, the broken families, the unsightly veins… because no one talks about these things publicly here. When it is discussed it is very “Hush! Hush!” and “What would the neighbours think!”. And this has a compounding effect, because these kinds of social ills fester and grow in these conditions.

I should not forget to mention, in passing, the teasing and sexual exploitation these group faces. “Sugar factory” is a common pet name for the more effeminate types on the low-end of the sex-trade pay, which averages to about 20-50 rupees (less than a dollar CAD) for a hand job.

We ask if it is possible to visit Mumbai’s biggest Red Light District, Kamathipura, but the transgender office worker tells us that she is concerned about negative backlash if she brings us without testing the waters first.

The talks wind down and we head out for a visit of one of the outreach sites: the Oval Garden, in Colaba. It is a huge fenced in park, in the heart of South Mumbai, where people play cricket and take leisurely strolls by day, and wander in search of some warmth at night.

The park is divided between MSMs, Transgender and Female Sex Workers. As we meander through, it is easy to spot couples sitting on the ground or groups of 2-3 people sitting on benches and by the packs of shrubs. The peer-outreach worker interrupts two TG’s who are talking with a gentleman, so we may ask them some questions. I feel awkward for disturbing them. It’s like a freak show tour. We hang around another half-hour or so, roaming around in the dark grass, and Pallavi graciously puts my on my train home. It’s great for the ego to need to be mothered by a twenty-something.

Meet Pallavi.

Thursday, March 27, 2015

As determined as I am to take the local train, I’ll admit I’m not yet up to speed with Mumbai’s railway system. Getting to the Mastana Office on the other side of town, in Vikhroli, seemed like a highly improbably venture, so I grabbed a rickshaw. It is my experience so far that only 30% of rickshaw drivers actually know where they are going, they tend to stop and ask fellow drivers along the way. It makes for some rather interesting conversations starters on the highway.

I met Pallavi on the East side of the station and we navigated our trajectory down smelly fish-vendor alleyways, until our rendez-vous point with Swapnil and Ram, two of the center’s outreach workers.

The Mastana office is tucked away in a maze of small streets that house, in my estimates, at least thirty or so families. Young kids run throughout the alleyways and stare up at me suspiciously, so do the aunties sitting on the front porches.

Ravindra, the site’s counsellor, tells us that this particular office only caters to MSM (Men who have Sex with Men) and that a lot of advocacy work has been done with the neighbouring families to raise awareness and explain the programs being promoted at the center. He says relations are good, in general. People in the area don’t mind the influx of strange men that follow their feet through their concrete jungle housing lanes.

Until 2011, the office was funded by different agencies, and eventually included into MDACS at the national level because the population it services is considered at a high-risk of infection. Outreach workers survey 8 train stations, from Kurla to Mulund on the Central line.

Of 1,185 registered clients, 980 are currently active. When a client becomes a no-show for 6 months, he is dropped out of the registration list. We are told that a number of the clients are migrant workers, living in rented flats, and they change sites depending on where work takes them. The office has had 20 HIV+ clients, 16 of whom are still active, 2 have migrated and 2 have passed away. Most of them get their treatments at the Sion hospital we visited earlier this week. On average, the counsellor says he sees 2-3 new cases of STI per month. They treat new patients on a referral basis where the first contact is with an outreach worker who provides information about prevention, and is then referred to a doctor or a counsellor.

It is a small, cozy space. The walls are filled with information posters, including a list of all the HIV clinics in the area, and a resource map that covers all the sites to help clients situate the services along the territory covered by peer and outreach workers. The site has developed a basic crisis-management response team, which can be quickly dispatched to specific locations when things get ugly.

List of organizational resources per district

Ravindra, who has been working at this office for over a decade, says he began as a peer outreach worker. He tells us they have a number of problems with police and local goons. The cops regularly pick up the outreach workers for keeping condoms in open spaces. Because the law enforcement staff keeps changing, it is difficult to keep advocacy efforts current. We are told there a three cops in the area that bait MSM’s in station bathrooms by pretending to be there looking for a hook-up. The scenario has become familiar to me by now. Beatings, extortion, blackmail, every one is looking for an opportunity to make a profit.

Vikhroli Station

In this case, however, Ravindra decided to take matters into his own hands. He investigated a grievance placed in the complaints box at the main HST office, which stated these police officers had roughed up an MSM and stolen a 10mg gold chain he was wearing. He decided to hand around one of the cruising sites until after 9pm, when his shifts normally ends, and gets picked up by the police. At the police station he confronts them about the incident, saying that they have lawyers who would like a word with them at HST. He asks them to attend a Friday workshop, which they do, and eventually manages to convince them not to harass his clients. “We need the money,” is the only excuse they offer. He shows me a photograph of one of the officers.

When peer workers warn people at sites about the police shakedowns in the washrooms, they are usually met with incredulity: “You just fancy whoever is in there, and you’re trying to keep me away.” They usually apologize on the way out.

A community stake-holder helps with the distribution of condoms outside the train station washrooms.

Despite the optimistic turn-around, I see a problem with accountability. The fact that the resolution of the problem has been one of accommodation, where cops now play favourites with who they harass or not, this state of affairs does not offer a tangible resolution of the issue. It simply puts a plaster on the problem, and shifts the burden on other victims, who have to find their own means of leveraging the situation.

Pallavi asks the counsellor about how he handles difficult cases, he tells us about one client who was diagnosed with HIV and became very aggressive when he was contacted for a follow-up. “Don’t ever call me again,” says the man over the phone. The counsellor proceeds to call him every other week, under threats of being beaten up, until finally he tires of the affronts. “Why do you think I am wasting my time calling you,” he asks, “because I care what happens to you.” Gradually, the client breaks down. He comes to the centre for the check-up during the off-hours, so no one sees him.

As Ravindra tells us his story, the rest of the outreach workers get ready. The combs and pocket mirrors are out, and a whirlwind of activity goes on in the background. I am easily distracted, and constantly feel like I am missing out on important parts of the story, as translations only come when the counsellor takes a pause, which isn’t of very often.

Ravindra moves on to the more subtle part of counselling work, like wondering if you should call a transgender “he” or “she” and dealing with clients who don’t aren’t open to counselling. “There was this one case,” he tells us, ”where there was a very quiet Khoti, who would frequent the sites, but would never talk to anyone. So when I approached him, I started with some small-talk, told him I liked his watch, gave him a card, told him about what we do, what we have to offer…and then I let him be. And every time I was him after that, I would make a bit more leeway.” The client asks him to break the news to his parents. He agrees to visit the client’s home. Where he meets the mother, then eventually the father. The client admits to being HIV+, and to being gay. Ravindra answers all their questions, puts their anxieties to rest. And while I wouldn’t say the story has a happy ending, because the man will end up succumbing to the disease, I’d like to think it is a step in the right direction.

Monday, March 23, 2015

This week’s field visit brings Pallavi and I to the dermatology department at Sion hospital, which specializes in STI (Sexually Transmitted Infections) treatment.

We are supposed to meet an MSM client who has been HIV+ since last January and has now been diagnosed with syphilis. We wait all morning. He never shows. The counsellor, Harish, tells us that this is the 3rd visit his client has missed this month. Proof that you can bring a horse to water, but you can’t force it to drink. Apparently, the man is also addicted to MDMA, and Harish suspects his absenteeism is linked to his substance abuse.

I count approximately thirty people waiting outside the office. Men, women, and children, all sitting uncomfortably on wooden benches, clutching their registration sheets. As I look up from the doctor’s desk, I notice the clock in the upper left corner of the room has stopped, as will all the others I notice that day. Beside it, there is a placard with the name of the doctors who work in the office, and a mention of the NGO. Only the sign reads “Hum Safer Trust”, instead of Humsafar. It makes for a strangely appropriate typo.

The Suraksha (prevention) clinic opened in 1999, as a joint initiative between HST and the hospital, and currently treats 80 people, at an average of 6 or 7 patients a day.

Harish gets a call on his mobile from a young man who wants to come in for preventive treatment, his Saturday night date having turned into a disaster on account of a broken condom, but mostly because the status of his partner is unknown. The patient will be ingesting his second dose of Azithromycin (1mg) before breakfast, and Cefixime (400mg) after lunch. This treatment kit is part of NACO’s prevention initiative, and apparently cures the symptoms of Gonorrhoea and Chlamydia within 4 or 5 hours, even if the latent infections can still be transmitted to another person for a period of 7-10 days following the initial dose. Harish tells us that most of his clients will use condoms when having anal sex, but rarely for oral. This increases the risk of infection because some of these diseases can be passed on through bacteria in the throat.

In other news, Hepatitis C, which had not been reported since January 2014, has resurfaced amid 4 new cases, all of which were MSM who interacted with multiple partners while taking part in orgies.

The hospital also houses an HIV-care clinic, operating according to NACO’s guidelines, which keeps track of the antiretroviral treatments taken by every patient. The centre also offers treatment for secondary ailments like jaundice or tuberculosis, which can be tricky to get rid of once your immune system is shot.

More than 40,000 people walk through these doors every year, and I wonder how many of them keep making it out. I can’t help but stare at a young mother, mid-twenties, as she holds fast her toddler while reaching for her registration sheet with the other hand. I wonder about the future of these people who, despite the fact that we have stabilized AIDS in a North American context, will probably never be given anything else than the generic versions of the drugs they desperately need to keep them alive.

Back in the early days hospitals used to identify HIV+ patients with special plates above their beds. This was seen as a controversial matter because families are still often kept in the dark. It was also seen as an open invitation for discrimination. When I enquire about end-of-life care facilities, and I am told that there are 2 NGOs in the greater Mumbai area who deal with terminal HIV patients. The counsellor, however, is sceptical about the quality of the care provided by these establishments and he tells me that, mostly, “no one takes care of them.”

Confidentiality is paramount in this business, as most of the clients still aren’t out to their families, despite being infected. “They usually find my contact info on the Humsafar Trust website,” says Harish.

It isn’t until a client’s white blood cell count falls below 300 (the normal range being between 4,000 and 11,000 per cubic millimeter of blood) that families are notified, either through an invitation to attend the clinic or a home visit. Harish affirms that with a healthy and balanced lifestyle, most patients can expect to live another twenty years following a positive diagnosis. I am told, however, that Indians don’t have a big pharmaceutical culture, and that getting patients to abide religiously by their posology is problematic. Nevertheless, most meds at government hospitals are distributed freely, which minimizes the risk of patients being given drugs that don’t suit them, at least for the likely few who could afford them.

Luckily, the super strain of the HIV virus (H2) has not yet spread in India, with only 6 or 7 cases being reported in the last 5 years. Harish believes most of these patients contracted the disease overseas, in Saudi Arabia or the UK.

Still, there are other, more personal, considerations to address, like a self-conscious transgender woman who is shy about meeting a doctor alone and needs to be attended to. Harish tells us that most hijras only show up for treatment when they have reached an advanced stage and can no longer manage on their own. Usually part of a community, or a hijra house, these ailing patients are often handed a one-way bus ticket by their gurus, and told to go back to their families to die.

Patient reactions range from dispassionate composure, blaming it on fate and what has been marked as inevitable in your stars, to utter and total emotional distress. Others just get angry, flush their meds down the toilet, and drown their sorrows in bouts of alcoholism, which weakens their immune systems even further. And yet getting people’s info to do follow-ups remains the clinic’s main challenge. I am told that between the fake addresses, temporary phone numbers, photo-less registration cards, and people who seem to vanish overnight, keeping an accurate track-record of the walking dead is a grim prospect at best.

A survey done by the HST revealed that the 18-28 demographic currently has the highest rate of infection. Perhaps this is because there is a misconception that people you meet online are cleaner, more honest. Even more distressing than this belief is the tendency among resentful MSM HIV+ patients to start recruiting younger partners and convince them to have unprotected sex. “No one made me aware before they infected me,” they argue, “so why should I?” With empathy and compassion so alarmingly depleted, the vicious circle continues, and steadily keeps on growing.

To illustrate this point, we are given the example of a 21-year-old who got tangled up with an older gay couple. For several months they would get the youth liquored up every Saturday night and reassure him into having unprotected sex. When a few of his friends decided to go for a routine test, he tagged along, only to discover that he was now HIV+. He claims the couple were the only two sexual partners he ever had. I think of all the wasted lives, and it makes me angry.

Out of desperation, I ask the counsellor how he gets through to his clients, when the odds seem so clearly stacked against him. He tells me he has this technique he favours, which consists of putting a condom on his two forefingers and sweeping it across his desk. He then shows it to the client and says, “See, you thought this desk was clean, but look at all this dust I’ve picked up – still, my fingers are protected.” Perhaps it isn’t the most hard-hitting of metaphors, but a big part of me sure hopes it drives the point across, for everyone’s sake.

#SundayFriends...too bad we're Monday I guess.