Thursday, March 27, 2015

As determined as I am to take the local train, I’ll admit I’m not yet up to speed with Mumbai’s railway system. Getting to the Mastana Office on the other side of town, in Vikhroli, seemed like a highly improbably venture, so I grabbed a rickshaw. It is my experience so far that only 30% of rickshaw drivers actually know where they are going, they tend to stop and ask fellow drivers along the way. It makes for some rather interesting conversations starters on the highway.

I met Pallavi on the East side of the station and we navigated our trajectory down smelly fish-vendor alleyways, until our rendez-vous point with Swapnil and Ram, two of the center’s outreach workers.

The Mastana office is tucked away in a maze of small streets that house, in my estimates, at least thirty or so families. Young kids run throughout the alleyways and stare up at me suspiciously, so do the aunties sitting on the front porches.

Ravindra, the site’s counsellor, tells us that this particular office only caters to MSM (Men who have Sex with Men) and that a lot of advocacy work has been done with the neighbouring families to raise awareness and explain the programs being promoted at the center. He says relations are good, in general. People in the area don’t mind the influx of strange men that follow their feet through their concrete jungle housing lanes.

Until 2011, the office was funded by different agencies, and eventually included into MDACS at the national level because the population it services is considered at a high-risk of infection. Outreach workers survey 8 train stations, from Kurla to Mulund on the Central line.

Of 1,185 registered clients, 980 are currently active. When a client becomes a no-show for 6 months, he is dropped out of the registration list. We are told that a number of the clients are migrant workers, living in rented flats, and they change sites depending on where work takes them. The office has had 20 HIV+ clients, 16 of whom are still active, 2 have migrated and 2 have passed away. Most of them get their treatments at the Sion hospital we visited earlier this week. On average, the counsellor says he sees 2-3 new cases of STI per month. They treat new patients on a referral basis where the first contact is with an outreach worker who provides information about prevention, and is then referred to a doctor or a counsellor.

It is a small, cozy space. The walls are filled with information posters, including a list of all the HIV clinics in the area, and a resource map that covers all the sites to help clients situate the services along the territory covered by peer and outreach workers. The site has developed a basic crisis-management response team, which can be quickly dispatched to specific locations when things get ugly.

List of organizational resources per district

Ravindra, who has been working at this office for over a decade, says he began as a peer outreach worker. He tells us they have a number of problems with police and local goons. The cops regularly pick up the outreach workers for keeping condoms in open spaces. Because the law enforcement staff keeps changing, it is difficult to keep advocacy efforts current. We are told there a three cops in the area that bait MSM’s in station bathrooms by pretending to be there looking for a hook-up. The scenario has become familiar to me by now. Beatings, extortion, blackmail, every one is looking for an opportunity to make a profit.

Vikhroli Station

In this case, however, Ravindra decided to take matters into his own hands. He investigated a grievance placed in the complaints box at the main HST office, which stated these police officers had roughed up an MSM and stolen a 10mg gold chain he was wearing. He decided to hand around one of the cruising sites until after 9pm, when his shifts normally ends, and gets picked up by the police. At the police station he confronts them about the incident, saying that they have lawyers who would like a word with them at HST. He asks them to attend a Friday workshop, which they do, and eventually manages to convince them not to harass his clients. “We need the money,” is the only excuse they offer. He shows me a photograph of one of the officers.

When peer workers warn people at sites about the police shakedowns in the washrooms, they are usually met with incredulity: “You just fancy whoever is in there, and you’re trying to keep me away.” They usually apologize on the way out.

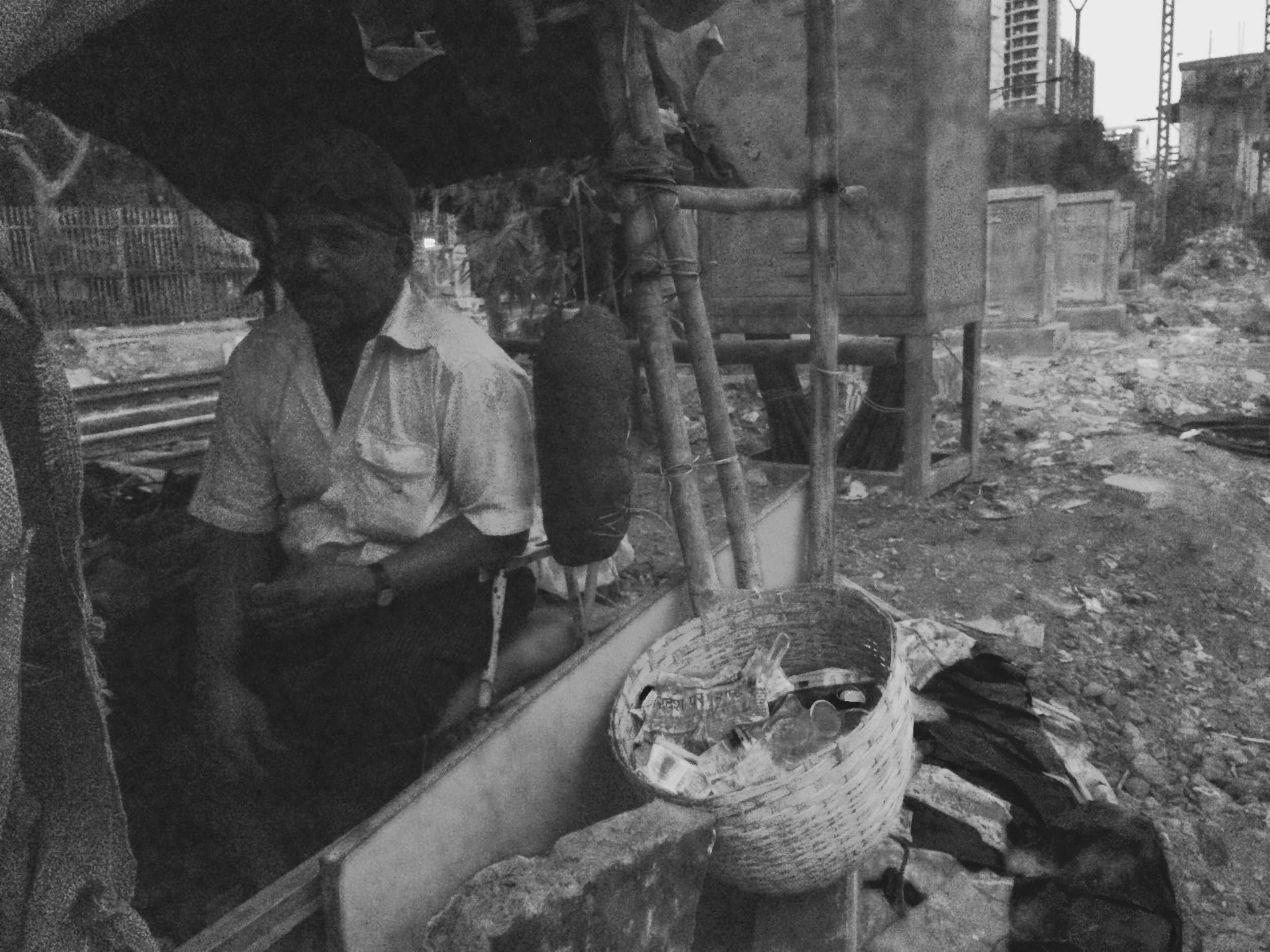

A community stake-holder helps with the distribution of condoms outside the train station washrooms.

Despite the optimistic turn-around, I see a problem with accountability. The fact that the resolution of the problem has been one of accommodation, where cops now play favourites with who they harass or not, this state of affairs does not offer a tangible resolution of the issue. It simply puts a plaster on the problem, and shifts the burden on other victims, who have to find their own means of leveraging the situation.

Pallavi asks the counsellor about how he handles difficult cases, he tells us about one client who was diagnosed with HIV and became very aggressive when he was contacted for a follow-up. “Don’t ever call me again,” says the man over the phone. The counsellor proceeds to call him every other week, under threats of being beaten up, until finally he tires of the affronts. “Why do you think I am wasting my time calling you,” he asks, “because I care what happens to you.” Gradually, the client breaks down. He comes to the centre for the check-up during the off-hours, so no one sees him.

As Ravindra tells us his story, the rest of the outreach workers get ready. The combs and pocket mirrors are out, and a whirlwind of activity goes on in the background. I am easily distracted, and constantly feel like I am missing out on important parts of the story, as translations only come when the counsellor takes a pause, which isn’t of very often.

Ravindra moves on to the more subtle part of counselling work, like wondering if you should call a transgender “he” or “she” and dealing with clients who don’t aren’t open to counselling. “There was this one case,” he tells us, ”where there was a very quiet Khoti, who would frequent the sites, but would never talk to anyone. So when I approached him, I started with some small-talk, told him I liked his watch, gave him a card, told him about what we do, what we have to offer…and then I let him be. And every time I was him after that, I would make a bit more leeway.” The client asks him to break the news to his parents. He agrees to visit the client’s home. Where he meets the mother, then eventually the father. The client admits to being HIV+, and to being gay. Ravindra answers all their questions, puts their anxieties to rest. And while I wouldn’t say the story has a happy ending, because the man will end up succumbing to the disease, I’d like to think it is a step in the right direction.